NoMoreXOR

Update 04/09/2013 - NoMoreXOR is now included in REMnux as of version 4.

Have you ever been faced with a file that was XOR‘ed with a 256 byte key? While it may not be the most common length for an XOR key, it’s still something that has popped up enough over the last few months (1, 2, 3, 4) to make it on my to-do list. If you take a look at first the two links mentioned above you’ll see they both include some in-house tool(s) which do some magic and provide you with the XOR key. Even though they both state that at some point their tools will be released, that doesn’t help me now.

Most of the tools I came across can handle single byte - four byte XOR keys no problem (xortool, xortools, XORBruteForcer, xorsearch etc.) but other than that I didn’t notice any that would handle (or actually work) with a large XOR key besides for (okteta, converter and cryptam_unxor).

I noticed Cryptam’s online document analysis tool had the ability to do this as well so I sent them a few questions on their process and received a quick, informative response which pointed me to a post on their site. Within the post/email they said that they don’t perform any bruteforcing on the XOR key but rather perform cryptanalysis and then brute force the ROL1-7 (if present). As shown in the dispersion graphs they provide, they appear to essentially be looking for high frequencies of repetitive data then using whatever appears the most to test as the key(s).

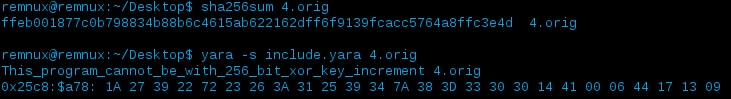

So how do you know if the file is XOR’ed with a 256 byte key in the first place? Well… you could always try to reverse it but you may also be lucky enough to have some YARA rules which have some pre-calculated rules to help aid in this situation. A good start would be to look at MACB’s xotrools (previously linked) and also consider what it is you might want to look for (e.g. - “This program cannot be run”) and XOR it with some permutations.

Manual Process

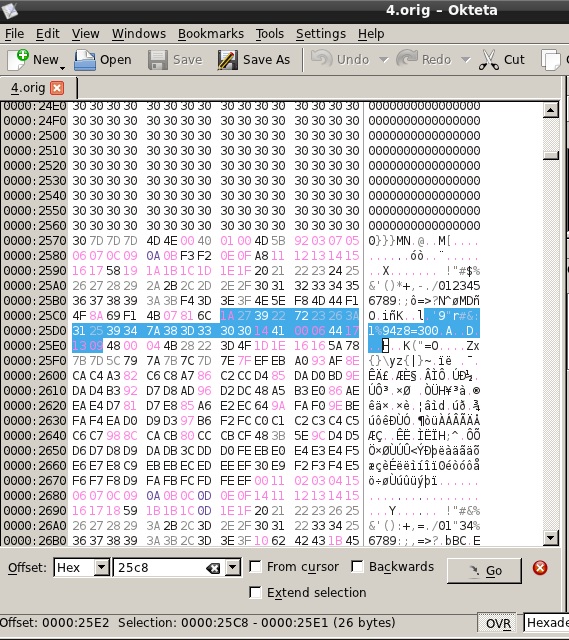

If we open that file within a hex editor and go to the offset flagged (0x25C8) we’ll see what is supposedly “This program cannot be run” = 26 bytes :

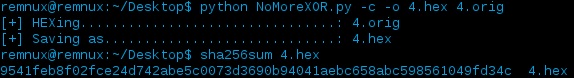

If we take that original file and covert it to hex we’ll essentially just get a big hex blob:

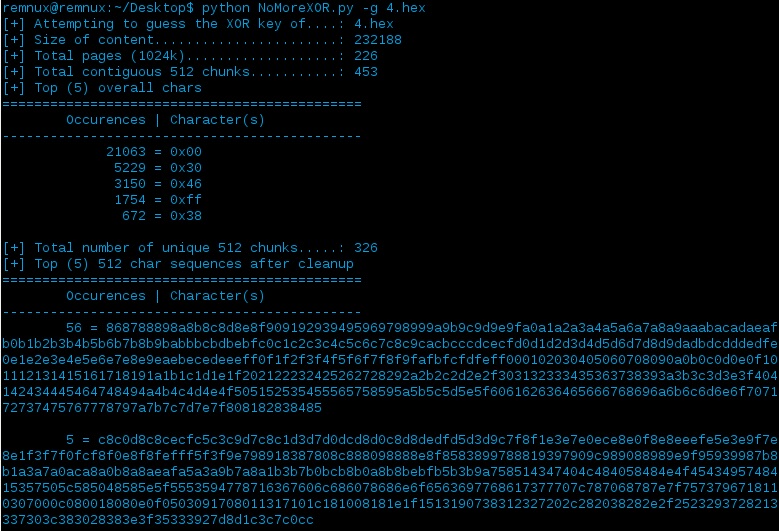

…but that hex blob helps to try and guess the XOR key:

From my initial tests, the XOR key has always been in the top returned results, but even if you’re having some difficulties for whatever reason you can always modify the code to fit your needs - gotta love that.

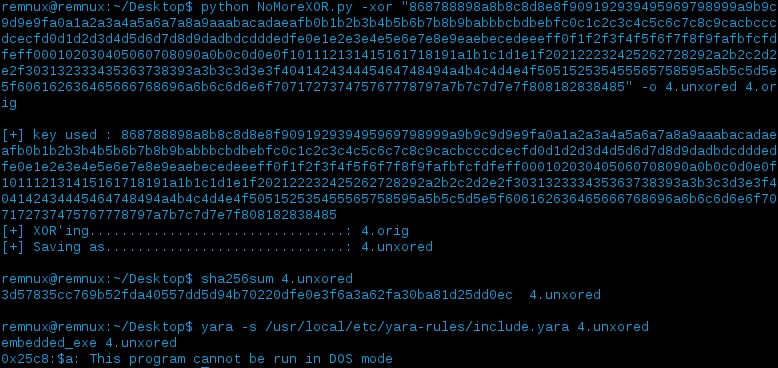

So if we now try to unxor the original file with the first guessed XOR key (remember XOR is symmetric) hopefully we’ll get the original content that was XOR’ed:

After the original file was unxored and scanned with YARA we see that it was flagged for having an embedded EXE within it (this rule can be found within MACB’s capabilities.yara file) so it looks like it worked.

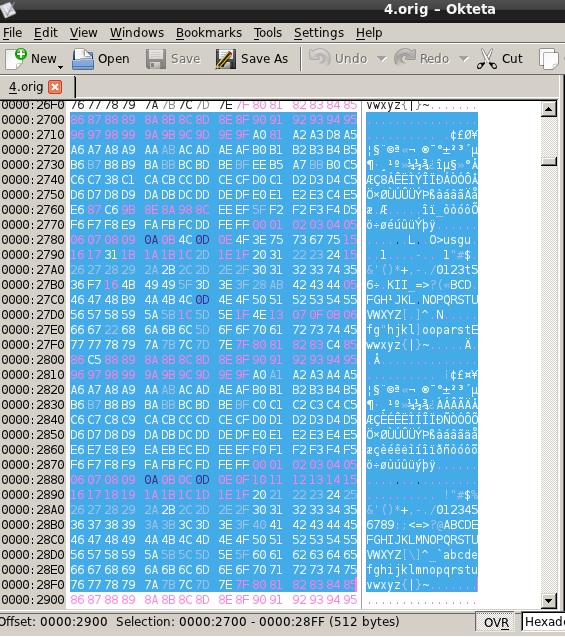

Now while all this hex may look like a bunch of garbage at times, the human eye is very good at recognizing patterns - and when you look more and more at things like this you’ll start to recognize them. Do you recall the YARA hit that triggered? It stated that the XOR key was incremented. What this means is that each byte is being XOR’ed with the next byte in an incremental fashion until it wraps back around to the beginning. That may be confusing the grasp at first so lets visualize it by breaking down the previously found 256 byte XOR key in its’ respective order:

868788898a8b8c8d8e8f 909192939495969798999 a9b9c9d9e9f a0a1a2a3a4a5a6a7a8a9 aaabacadaeaf b0b1b2b3b4b5b6b7b8b9 babbbcbdbebf c0c1c2c3c4c5c6c7c8c9 cacbcccdcecf d0d1d2d3d4d5d6d7d8d9 dadbdcdddedfe 0e1e2e3e4e5e6e7e8e9 eaebecedeeef f0f1f2f3f4f5f6f7f8f9 fafbfcfdfeff 000102030405060708090 a0b0c0d0e0f 10111213141516171819 1a1b1c1d1e1f 20212223242526272829 2a2b2c2d2e2f 30313233343536373839 3a3b3c3d3e3f 40414243444546474849 4a4b4c4d4e4f 50515253545556575859 5a5b5c5d5e5f 60616263646566676869 6a6b6c6d6e6f 70717273747576777879 7a7b7c7d7e7f 808182838485

As you see, it started with 86 and looped all the way around till it reached 85 - you should also notice the patterns on each line. This is just an example of incremental/decremental XOR (not as commonly observed in my testing but useful to be aware of) but it’s useful to know because it’s quite easy to spot if you look at the original file in a hex editor again:

… and that’s a pattern that was observed repeating ~56 times.

Automated Process

So now we can kind of put together a process flow of what we want to do:

- Convert the original, XOR’ed file to hex

- Conduct some slight frequency analysis of the newly created hex file and look for the most common characters as well as the most commonly observed hex chunks.

- The first part may help in determining if there’s an embedded PE file (usually a lot of \x00’s) or possibly help deduce if certain bytes should be skipped.

- The latter essentially reads 512 bytes at a time, stores it and continues till the end of the file. Once complete it does some simple checking to try and weave out meaningless possible keys then presents the top five most observed 512 bytes or characters in this sense (i.e. - 512 characters = 1 possible 256 byte key(s))

- For each possible XOR key guessed from the previous step, XOR (the entire file for right now) the original file, save it to a new file and scan it with YARA.

- I chose to perform YARA scans here to help determine the likelihood that the key used was correct - you may choose to implement something else such as just a check for an embedded PE file etc. If there are YARA hits then I stop attempting the other possible XOR keys (if any other were still to be processed) and assume the previous XOR key was the correct one.

If you stick with the YARA scanning, it will continue to process all of the possible key(s) it outlined as the top, in terms of frequency, so your YARA rules should include something that might be present in the original XOR’ed file. If not, you might already have the correct XOR key but aren’t aware. Embedded exe’s are a good start to look for since they’re common - but remember if we XOR the entire file at once instead of a specific section that you might find the embedded content but that doesn’t mean the original file will be readable afterwards (i.e - won’t be a Word document anymore since it was XOR’ed)

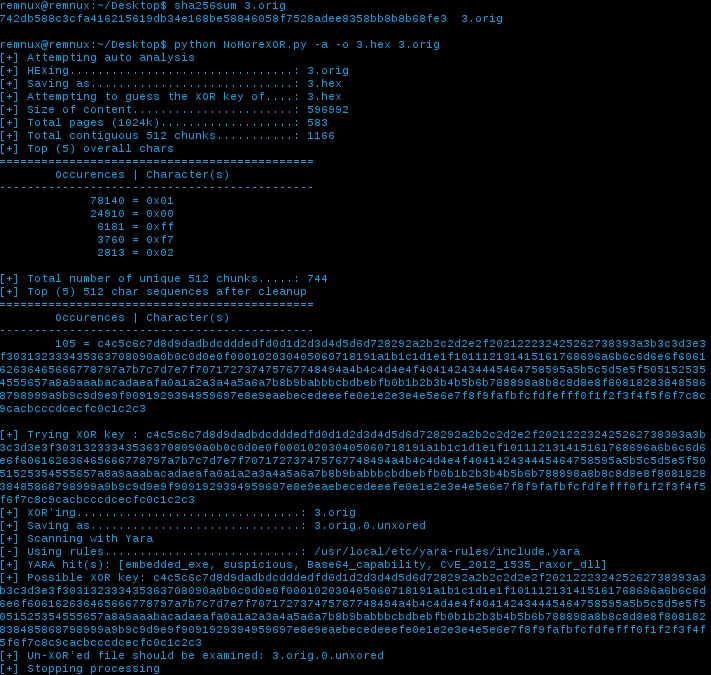

Let’s try out that process flow in a more automated way (on a new file):

As you can see, it worked like a charm ![]()

As always, I’m sure there’s a better way to code some of the stuff I did but hey, it works for me at the moment. There’s a to-do list of things that I want to further implement into this tool, some of which is already included in other tools. I’ve been asked before how this tools will work with smaller XOR keys and that’s up to you to test and tell me - I created this in order to tackle the problem solely of the 256 byte key files I was observing so I’d recommend using one of the earlier mentioned tools for that situation, at least for the time being.

To-Do’s

- ROL(1-7)/ROT(1-25) - either brute forcing or via YARA scans

- Add ability to skip \x00 & other chosen bytes (ref)

- more is outlined within the file….

Download

NoMoreXOR can be found on my github